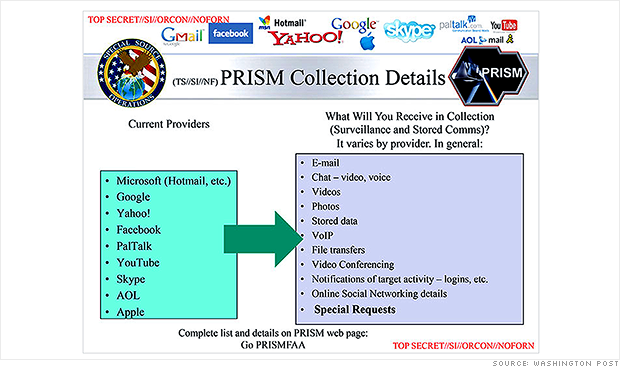

The Guardian and The Washington Post uncovered PRISM through leaked documents.

The Guardian and The Washington Post uncovered PRISM through leaked documents.The U.S. government reportedly has a sweeping system for monitoring emails, photos, search histories and other data from seven major American Internet companies, in a program aimed at gathering data on foreign intelligence targets. But the companies say they didn't know a thing about it.

That's one of

the biggest conundrums of the newly discovered National Security Agency

surveillance program known as "PRISM": If Microsoft (MSFT, Fortune 500), Yahoo (YHOO, Fortune 500), Google (GOOG, Fortune 500), Facebook (FB), PalTalk, AOL (AOL), Skype, YouTube and Apple (AAPL, Fortune 500) really didn't know, how did the NSA get the data?

Theory A: It ain't what the papers say it is. The Guardian and The Washington Post may have overstepped in their analysis of the PowerPoint-style slides they obtained from an NSA source. There's a chance PRISM isn't the wide-ranging program that they reported it to be.

The Washington Post altered part of its article on Friday, removing a line saying that the tech companies "participate knowingly in PRISM operations," and both newspapers are vague about just how much data is being amassed.

The quotes they use sound scary: "They quite literally can watch your

ideas form as you type," the "career intelligence officer" who exposed

the program told the Post.

But can "they" -- meaning the NSA -- do that for everyone, or only for targets that they have obtained court orders to pursue? All of the tech companies listed in the Guardian and Post articles make clear in their service terms that they will hand over user data when legally compelled to do so, but several insisted very strongly that they have no "back door" system giving the government unfettered access.

" Any suggestion that Google is disclosing information about our users' Internet activity on such a scale is completely false," Google CEO Larry Page wrote in a blog post titled "What the ...?"

If PRISM still requires the government to get a court order before

obtaining the information, that could explain why the companies didn't

know about the program -- they're accustomed to receiving subpoenas from

the government for users' data, on a limited scale.

Theory B: PRISM exists as the newspapers said, and the companies -- or at least an employee or

two -- knew.

The NSA's tremendous capabilities have been well documented by news outlets like Wired, which last year revealed the existence of a massive Utah data center and a secret NSA code-cracking supercomputer in Tennessee. A program like PRISM isn't difficult to imagine, and it's possible that the companies did, in fact, know about it.

All of seven of the tech companies named in the slide presentation came out with strongly worded denials. But Mike Janke, the CEO of encrypted communications service Silent Circle, thinks the companies were compelled to grant significant access to their systems based on post-Sept. 11 amendments to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978, which targets foreigners of interest to the government.

"[The tech companies] are wordsmithing -- they didn't know it was called PRISM, maybe, but they were asked to provide access," Janke told CNNMoney. "Otherwise the government would be sending subpoenas every five seconds."

Janke said he's "100% sure" the government had access to the servers somehow. A telltale sign: virtually all digital communications feature some form of encryption, but the government reportedly had access to decrypted data. Most often, the encryption key is located on a company's server.

"Looking at the type of data that was included -- video chats, full emails -- the only way you can get that is by being in a [company's] central server," Janke said. "No question about it."

But the companies' denials are so firm that it seems unlikely they're all playing word games. It's possible that only a small number of people at the companies knew about the government access, noted John

Michener, chief scientist at Casaba Security. Since the program was top-secret, the news could have surprised even the CEOs of firms that complied.

"It could have been an engineer or two asked to put in some special equipment, and they're court-ordered not to say anything," Michener said. "And then the CEO can say, 'Of course we didn't know!'"

If the NSA did finagle its way into the company's servers directly, someone must have known about it because it leaves a trail that's difficult to erase, said Mark Wuergler, a senior researcher at security consultancy Immunity Inc.

"If the NSA gets into your system somehow and removes all of this information, that's millions of records," Wuergler said. "That creates a massive paper trail. There's a log showing you that it happened."

Theory C: The companies didn't know, and the NSA got the data anyway. The Post cited a separate classified report that claims the mining is done through networking equipment, such as Internet routers, installed at the companies' offices. Similarly, some security experts suggested the NSA could have put its own intercept devices between the companies' data centers and the wider Internet.

The NSA has a history of doing that kind of thing. The existence of "Room 641A," a secret intercept operation installed in an AT&T (T, Fortune 500) data center in San Francisco, came to light in 2006 after a whistleblower went public.

Access through NSA-monitored equipment is a possible scenario, Wuergler said. But the companies almost certainly would have discovered what was happening in short order.

"That would be a very noisy attack," Wuergler said. "If that's what was done, and the companies truly didn't know about it, that would be a major security breach."

Wuergler said the public shouldn't be surprised by this kind of widespread monitoring. He pointed to President Obama's statements Friday about the delicate balance between privacy and protection. In short, we can't have 100% of both.

"I think that the NSA, of all agencies, has more access to our private lives than we think," Wuergler said. "It's when these little details come out that we start to panic."

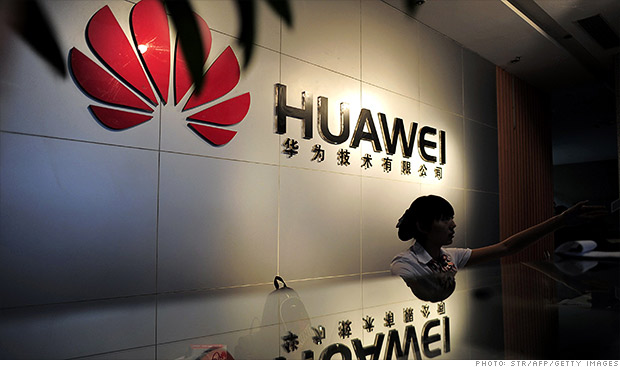

U.K. lawmakers have been probing Huawei's position at the heart of the country's telecoms network.

U.K. lawmakers have been probing Huawei's position at the heart of the country's telecoms network. The U.K. should monitor the operations of Chinese telecom Huawei within its borders more closely to reduce the risk of cyberattacks, according to a parliamentary report published this week.

The Intelligence and

Security Committee found significant failings in the way the U.K. tries

to protect national security while encouraging foreign investment in

strategic infrastructure such as telecom, energy, and transport

networks.

Huawei's transmission and access equipment plays a critical role at the heart of the U.K. telecom network. Under a contract signed with market leader BT, the Chinese firm began deploying its equipment in 2007.

China's largest telecom firm operates in more than 140 countries and generates over 70% of its revenue outside China. Yet it has been shut out of the market for networks in the U.S. and Australia over concerns that it could open the door to hackers or spies from China -- charges Huawei strenuously denies.

The U.K. committee said most concerns surrounding Huawei relate to its perceived links to the Chinese state, which generate suspicion as to whether Huawei's intentions "are strictly commercial or are more political."

"Whether the suspicions are legitimate or unfounded, we consider it necessary to ascertain how Huawei came to be embedded in the heart of critical national infrastructure," the report stated.

The lawmakers said that, theoretically, the Chinese state may be able to exploit vulnerabilities in Huawei's products to gain access to the BT network for spying.

Huawei and the U.K. government sought to minimize that risk by creating a cyber-security evaluation center, known as the Cell, in 2010. The Cell -- run by Hauwei employees vetted by U.K. security services -- tests all Huawei software and hardware updates for high-risk components before they are deployed.

The report found that U.K. intelligence agencies have confidence in BT's management of its network, but said risk could not be eliminated entirely.

It urged the government to carry out an urgent review of the effectiveness of the Cell, and called for greater oversight of its operation by the intelligence agencies and more involvement by government in the selection of its staff.

Huawei, which employs 890 people in the U.K., said it has the full support of the U.K. government and its customers, including BT.

"Huawei is willing to work with all governments in a completely open and transparent manner to jointly reduce the risk of cyber security," it said in a statement.

Judge Cote may be backing away from her preliminary view of the DOJ's antitrust case.

Judge Cote.

Via dealbreaker.com

FORTUNE -- A subtle but potentially important shift took place Thursday in the Manhattan federal courthouse where U.S. District Judge Denise Cote just wrapped up the first week of the three-week civil antitrust case known as U.S.A. v. Apple.

Via dealbreaker.com

FORTUNE -- A subtle but potentially important shift took place Thursday in the Manhattan federal courthouse where U.S. District Judge Denise Cote just wrapped up the first week of the three-week civil antitrust case known as U.S.A. v. Apple.

One of the central questions in the case is whether Apple (AAPL) executives told the six biggest book publishers they had to change the way they did business with Amazon (AMZN) or whether the publishers came to that conclusion because of the clever way Apple structured its contracts. (See The "lynchpin" of Apple's e-book strategy.)

On Thursday, Laura Porco, one of the Amazon executives who negotiated deals with book publishers, submitted a written statement that strongly suggested the former. In it she testified that the week before Steve Jobs announced the iBookstore, five of the six major publishers told her that "they were requiring Amazon to switch its terms ... because that's what Apple required them to do."

That looked pretty damaging to Apple.

But before Porco was allowed to leave the witness stand, Judge Cote,

who alone will decide the non-jury case, had a few questions.

She zeroed in on the next sentence in Porco's written testimony:

"[The publishers] said their agreement with Apple included restrictions around consumer pricing that made it technically impossible to remain on reseller terms with Amazon or any other retailer."

Could those "restrictions" be what the publishers were referring to

when they said Apple "required" them to change their terms? Judge Cote

asked Porco. In other words, were the publishers' longstanding deals

with Amazon off because of the structure of their agreement with Apple, not direct instructions from Apple?

The lawyers at Apple's table snapped to attention.

It was the first time in four days of trial that the judge -- who in pre-trial statements

seemed to have already decided the case against their client -- asked a

clarifying question that not only favored Apple, but seemed to get to

the heart of its defense.

Orin Snyder, Apple's lead attorney, seized his advantage with the next witness.

Thomas Turvey was the Google (GOOG)

executive who signed contracts with the same publishers before Google

launched its own e-bookstore later that year. Google had been

negotiating deals with the publishers under terms similar to Amazon's,

using the so-called wholesale model where Amazon set the price of

e-books. Apple's contracts called for "agency" arrangements, where the

publishers set the price and Apple took a 30% cut. Both Amazon and

Google much preferred the wholesale model.

In his written statement, Turvey testified that in January 2010 that

representatives of the five publishers told him that they were switching

from a wholesale to an agency model.

"In addition," he continued, "each of the publishers either advised me directly or strongly implied that their agreements with Apple ... did not allow them to continue offering their books under wholesale terms." (emphasis added)

In his deposition, it turned out, Turvey said something different -- that the publishers could no longer sign wholesale deals "because of their agreements with Apple."

In questions that grew increasingly hostile, and at times almost brutal, Apple's lawyer got Turvey to admit that he couldn't remember the names of any of the publishers who told him Apple "did not allow" wholesale. He couldn't remember any of the phone calls or meetings when the conversations took place.

Had no notes to support his recollection. Did not e-mail Google headquarters to relay the important news. And couldn't even swear that he had written the words that appeared in his direct testimony, because the entire document -- submitted under oath -- was "constructed with counsel."

That is to say, the words could have been written not by Turvey, but by Google's lawyers.

Turvey, who looked shaken when he hurried out of the courtroom, returns to the stand on Monday. It will interesting to see whether Judge Cote has any follow-up questions for him.

NOTE: For a backgrounder on the legal issues in the case, you can't do better than my colleague Roger Parloff's US v. Apple could go to the Supreme Court.

There are parallels between today's trolls and the so-called sharks of the 19th century.

FORTUNE -- Complaints about patent trolls have reached such a level that the White House is now pushing for reform. Some people might believe the problem to be relatively new. And it is, in a way. But there were patent trolls in the 19th century, and they behaved in much the same way as modern ones, causing railroads and farmers to form trade groups to protect themselves. Back then, the trolls were called "sharks."

A fascinating recent paper issued by the Yale economics department shows several parallels between that time and our time. Then, as now, the trouble really started as soon as the lawyers got involved. And the economic conditions were similar: Unlike during the heyday of corporate research and development in the mid-20th century, the market for software patents is largely made up of small firms, just as there were a lot of independent inventors in the mid- to late-19th century. Now, as then, there is the problem of informational asymmetry to contend with. And the functions of software, like those of many of that era's inventions, are often broad and vaguely defined. (The paper is titled "Patent Alchemy: The Market for Technology in U.S. History. The authors are Naomi R. Lamoreaux, Kenneth L. Sokoloff, and

Dhanoos Sutthiphisal. It was published by Business History Review.)

In fact, the dominance of corporate R&D was the anomaly. There is "actually nothing new about the practice of extracting economic value from patents by selling off or licensing the rights," the authors note. "During most periods of U.S. history, it was as common for inventors to profit from their creativity in this way as by starting their own firms or working as salaried employees" in a corporate research division.

Not that selling or licensing off patents is by itself a problem. Thomas Edison "depended heavily on assignments to finance the early stages of his career," according to the paper. He transferred the rights to 20 of his first 25 patents. But the existence of a robust market for patents is what brings in the trolls, or sharks. Inventors who held on to and exploited their own patents represented less than a quarter of the patents issued in the late 19th century. The other three-quarters were up for grabs, and it was often rank opportunists or outright fraudsters who did the grabbing.

The lawyers swooped in after the passage of the Patent Act of 1836, when the government started examining patents to ensure there were no prior patents on the same technology. This created a need for expertise. Inventors also began hiring agents (often patent lawyers) to sell and license patents on their behalf in local markets around the country, as well as nationally. Most of these agents seem to have been legit, but a lot of them weren't. Some of them would sell patents that didn't actually exist. Others would sell or license them and not inform the inventors, keeping the fees or proceeds for themselves. Inventors

could market their patents themselves, but that was incredibly expensive and time-consuming.

Compared to the level of fraud, "sharks" were a relatively minor problem, but they affected the farming and railroad industries in a big way. One shark, Thomas Sayles, bought the rights to three patents on a railroad braking system. If a railroad licensed one of the patents, he would sue for infringement on one of the other two. The railroads joined up to take him on, winning a case before the Supreme Court in 1878. The Court's decision in effect limited the amount that sharks could get from lawsuits: "Infringers" were thereafter liable only for the incremental value they derived from employing a particular patented technology in lieu of possible substitutes.

Farmers weren't quite as successful in fending off the sharks, at least at first. "During the 1870s and '80s," the paper notes, "western farmers were deluged with threats of legal action" based on alleged infringement. The patents were often on "inventions" like barbed wire and milk cans. "These cases seem to have flourished because there was uncertainty about the value and legitimacy of many of the patents ...

" Many farmers formed associations to strengthen their legal fight. In many cases -- including the barbed-wire case -- they lost. "Nonetheless," the farmer's increasingly well-organized opposition took its toll on the sharks' business, "by forcing them to pay more to litigate and by the fact that the sharks' methods were publicized, giving them less political cover. By the 1890s, the problem had "largely abated," the authors note.

Patent trolling seems like a new phenomenon to many of us because most of us grew up during a time when corporations dominated the patent market. But the economic environment is much different now, and in important ways more like it was in the 19th century. In 1970, small firms owned just 5% of patents issued worldwide. By 1990, that had grown to about one-third, and it's growing still. As large firms looked for places to reduce costs, their R&D departments were often the first to have their budgets cut, and firms looked outside for new technologies. Between 1980 and 2005, the R&D expenditures of companies with 25,000 or more employees fell from about two-thirds of the total to about one third.

"As in the past, the growth of the market for technology has given rise to new problems of asymmetric information that opportunists can exploit to their advantage," the authors note. This is especially true of software, where the functions -- like those of barbed wire -- are wide-ranging and vague. Abstraction and multitudinous potential applications are inherent in software, and are just what a troll looks for when shopping around for someone to sue.

The authors conclude that "it is not clear that the 'troll' problem" today is "commensurately more serious than it was in the earlier period." But that conclusion is based on the level of success of cases that are decided in court: Most often, the trolls lose. But the authors themselves recognize that "trolls can still do a lot of economic damage just by threatening litigation." Terms of settlements aren't usually known, nor is the level to which patent trolls stifle innovation. It's clearly a lot.

Beyond government initiatives like those proposed by the White House, the authors expect the backlash against patent trolls to grow. "As in the late 19th century, one might expect defendants to revise their assessments of the probability of winning and start fighting more of these cases in court, perhaps again basing together in associations for that purpose."

In fact, that's already occurring. It could be that the panic we're seeing among champions of innovation is actually the beginning of the end of patent trolls, at least in the current era.

It's time for Apple to open up Apple TV to its vast third-party app system.

It's time for Apple to open up Apple TV to its vast third-party app system.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney)

If there was ever a time for Apple to open up its Apple TV platform to third-party apps, that time is Monday at Apple's annual Worldwide Developers Conference.

Sure, Apple is likely to give us the

first glimpses of iOS 7, Mac OS X 10.9, new MacBooks and its "iRadio"

music service. But significant as those are, there's little intrigue to

be had. Rethinking the Apple TV could provide some newness at Apple that

techies have been calling for, and it has the potential to restore a

little mystery to the Cupertino juggernaut.

It has seemed inevitable that Apple's vast array of app titles would pop up on the Apple TV ever since Apple (AAPL, Fortune 500) redesigned the device into a tiny "puck" that ran a variant of the iOS mobile operating system used on the iPhone and iPad. That happened in September 2010, and we're still waiting.

To be fair, there are

good reasons why Apple might have opted not to open up Apple TV to its

ecosystem of apps. Convincing developers to design an interface and

build an experience for a third device is no easy task. And it's not

like the Apple TV is a best-seller: The company has sold just 13 million of the devices since it debuted in 2007.

But timing now seems right for Apple to flip the app store switch.

Sales are accelerating: half of all Apple TVs have been sold over the past 12 months, CEO Tim Cook announced at an AllThingsD conference late last month.

The last two versions of the Apple TVs arrived a year and a half apart from one another (at the end of 2010 and beginning of 2012, respectively). Now, we're a year and a half since the latest update.

The hardware is more than capable of handling apps, since each

generation of Apple TV mirrors its iPhone counterpart in processing

power. Apple does feature a (very) small number of third-party apps

already, including Hulu, Netflix (NFLX), Google's (GOOG, Fortune 500) YouTube and several sports apps.

It's almost as if Apple is just waiting for just the right time to open the floodgates.

But if Apple waits too long, it runs the risk of ceding ground to the competition. Roku's streaming boxes continue to improve, Microsoft (MSFT, Fortune 500) is transforming the Xbox

into an all-purpose, home entertainment device, and Google remains

lurking in the shadows with its Google TV platform. And new companies

pop up every day promising to change television forever.

An app ecosystem on Apple TV could be a competition killer. Apple could open itself up to an untapped user base that might not want to shell out hundreds of dollars for iPhones and iPads but could be willing to pay $100 to dip their toes in the water.

One feature with major potential could be games. We've seen glimpses of how iPhone games on the TV might work with titles such as Real Racing 2, which can stream from an iPhone to a user's television through Apple TV. The technology is promising. Apple would likely have to develop a video game controller for the Apple TV, but there have been rumblings that one is in the works..

Opening up apps on the Apple TV could also serve as a testing ground for the fabled "iTV," a do-it-all television that everyone but Apple has promised is the path forward for television. An app-enabled Apple TV would give Apple engineers and third-party developers time to figure out what works and doesn't work in the living room before such a device ever arrives.

Most importantly, with the competition feverishly trying to plant its flag, opening up the Apple TV to developers could serve as a reminder to consumers that Apple is serious about the living room. It could convince people that the Apple TV is worth a hundred bucks after all.

Apple is now one of the most aggressive tech companies in adopting progressive environmental policies in China.

FORTUNE -- Ma Jun, the noted Chinese environmental activist, says Apple has gone in a short period of time from being the most uncooperative of electronics companies to "one of the most proactive IT suppliers" of all.

Speaking at a panel on supply-chain trends at the Fortune Global Forum in Chengdu, China, Ma practically gushed about Apple's change in behavior. He said that when his group, the Beijing-based Institute of Public & Environmental Affairs, initially approached 29 big Western brands about cooperating with its environmental work, 28 responded -- all but Apple. "They said they had a long-term policy against" participating with such groups. Things changed after Ma's group published two reports critical of Apple. "They approached us," he said. "They said, 'We need transparency.'"

Ma is a well-known former journalist who has devoted considerable energy to water issues in China. His group collects pollution data on Chinese companies and shares it with Western companies to help them better understand the ramifications of their supply chain partners. He said Apple not only has begun cooperating with his organization, it has become a positive force on the overall supply chain ecosystem in China.

"They have gone the furthest in motivating key suppliers," he said, noting that Apple has become even more aggressive than its IT-industry peers in adopting progressive environmental policies in China.

The change in attitude is so pronounced that Ma's institute published a third report earlier this year with an early section describing "Apple's Transformation." The bulk of the work Apple (AAPL)

has done began in 2012, after the death of Steve Jobs. It is generally

believed that Apple CEO Tim Cook, who has been traveling to China as a

supply chain executive for many years, has been supportive of Apple's

cooperation with environmental groups in a way that Jobs was not. Ma

said he has not met with Cook but that he has held meetings with other

high-level Apple executives.

Apple typically maintains that its environmental and labor-rights records have always been good. Yet the Chinese group's report makes clear that if nothing else, Apple's attitude toward discussing its record and opening itself up to criticism have changed. It's an intriguing window into how the company might change in other ways. It is notoriously secretive and closed to the type of mutually beneficial dialogues most other big companies conduct with each other, the press, and other groups that don't bear directly on making and marketing their products.

Empires changes their ways slowly, a topic that has been much debated about China at the Fortune conference in Chengdu. The same is true for Apple.

Firefox OS is a lightweight, inexpensive operating system for

phones being developed by the Mozilla Foundation, the group that makes

the popular Firefox web browser. Why is Firefox going in this direction?

After all, Apple (AAPL, Fortune 500) and Google (GOOG, Fortune 500) combined control over 90% of the mobile OS market. Attempts by Microsoft (MSFT, Fortune 500) and Blackberry (BBRY) to cement third place

-- with market share in the low single digits -- have proved expensive

and not-so-successful. Firefox OS isn't going after the top of the

market -- at least not yet. Introduced earlier this year, the operating

system is initially aimed at low-cost handsets in developing markets.

Firefox OS is based on Linux and is open source. It is designed to allow web-like HTML apps to directly control a device's hardware using JavaScript and so-called web API's. Mozilla's interest is in establishing or cementing web technologies, as opposed to some of the closed approaches of other big players. So far, initial Firefox phones have been low-frills affairs. But Taiwanese giant Foxconn -- the world's largest manufacturer of electronic devices -- is going to put some weight behind Firefox OS. (Foxconn, of course, puts together devices for Apple and Nokia (NOK).) Here's a closer look at the revolutionary operating system.

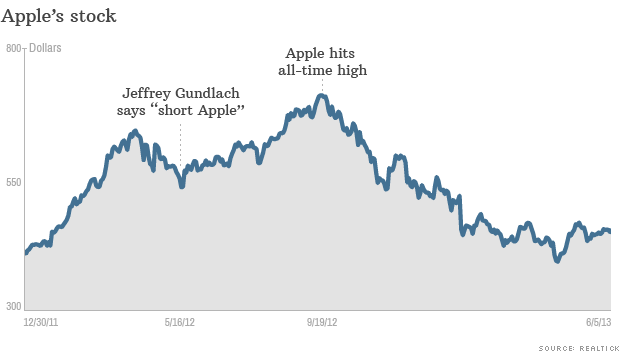

Hedge fund manager Jeffrey Gundlach says Apple's stock is now a good defensive play.

Hedge fund manager Jeffrey Gundlach says Apple's stock is now a good defensive play.The world has lost faith in Apple and Tim Cook, but fund manager Jeffrey Gundlach is a buyer.

That's a big shift for the Doubleline Capital CEO. Last May, when the world was still enamored with all things Apple, Gundlach made a bold pronouncement: short the stock.That was the turning point.

Since hitting that all-time high, the stock has fallen 37% and is down 18% from when Gundlach first said that he was shorting it.

Related: Bond gurus say Treasuries are still safe

Gundlach's firm oversees $60 billion of assets, and he's well known for his prescience in timing the ups and downs of the Treasuries market.

Now when he talks Apple (AAPL, Fortune 500), investors may be starting to listen.

"Apple has gone from being revered to nearly reviled," he said. "Now they are thought to be a tax avoider, and innovation is gone. The market has passed them by."

Gundlach's response to Apple has been more muted. He disliked the valuation last year, and since it fell below $425 in early March 2013, he's been a buyer.

"I don't have fantastic expectations for Apple, but I think it's a safe stock to own," he said.

Related: How Apple scores its lower tax bill

Moreover, he sees it as a hedge in his portfolio.

"It goes up when the market goes down," said Gundlach. "A lot of stocks look like they've carved out a top. I think Apple looks like it's carved out a base."

Gundlach says he'll remain a buyer of Apple at prices below $500. "It's cheaper than most stocks and is a solid cash flow engine for the foreseeable future."

Not all of Gundlach's short positions have worked out as well.

At this year's Ira Sohn conference in May, Gundlach recommended shorting Mexican eatery Chipotle (CMG). The stock is down a measly 2% since then.

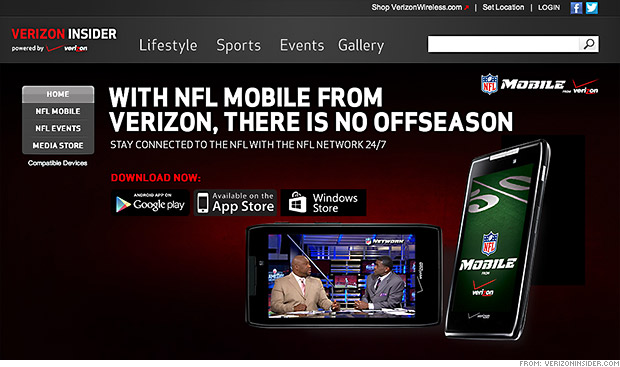

Verizon extended its exclusive deal with the NFL to stream live games.

Verizon extended its exclusive deal with the NFL to stream live games.Verizon extended its exclusive deal with the National Football League yesterday, which for the first time will include the ability for subscribers to stream Sunday afternoon games and playoffs on their phones.

Beginning in the 2014 season, football fans with Verizon (VZ, Fortune 500) phones will be able to watch the home-market feeds of CBS (CBS, Fortune 500) and News Corp.'s (NWS) Fox Sunday afternoon NFL games via Verizon's NFL Mobile app. The new deal also will allow Verizon customers to stream all playoff games, including the Super Bowl.Verizon customers will continue to be able to watch nationally televised games on Thursday night, Sunday night, and Monday night, which was part of the previous streaming deal inked between Verizon and the NFL.

The media-streaming deal will cost Verizon $1 billion over the next four years, according to Sports Business Daily. It was previously paying about half that amount annually.

That would make the new media-streaming deal one of the world's largest.

The field of broadcast shows signing deals with online partners has been steadily growing. In April, Yahoo (YHOO, Fortune 500) inked a deal with Comcast's (CMCSA) NBC to exclusively stream "Saturday Night Live" skits for one year.

Related Story: Will broadcasters beat Aereo at its own game?

For the 2013 season, Verizon will launch an updated version of its NFL mobile app which provides access to news, stats, game highlights, and on-demand videos in addition to live-streamed games. The basic, free app is available on phones and select tablets but does not provide access to live-streamed games.

Currently, Verizon customers must pay $5 monthly for the premium app allowing them to watch the games live -- a feature only available on phones.

The mobile dating game that lets you rate people by their looks is trying to shift into a tool for business networking.

How do I look?

FORTUNE -- Nope. Nope. Nope. YES! Nope…

That might be your thought process while using Tinder, a mobile app that offers up photos of people to judge with a "yes" or a "nope"—depending on their attractiveness. The iPhone app, which debuted in October, connects to Facebook (FB) and displays photos from a user's albums. Its genius is in the avoidance of outright rejection: when a users clicks "yes" to someone who has also liked them, it's a "match" and both users gain the ability to chat with each other. If nothing happens, the other person may simply have not seen you yet. Users never find out explicitly when someone clicked no.

That formula—in an era when online dating is growing rapidly—seems to work. According to a March report from IBISWorld, $1.13 billion or 56.3% of the international $2 billion-in-revenue "dating services" industry is online dating. Barry Diller's IAC (IACI), which owns Match.com and OkCupid, has a dominant 23.7% of that market; eHarmony is closest after that, with 13.6% of the dating services pie.

Unlike sites that provide a comprehensive dating profile (the average OkCupid user voluntarily answers 233 questions about themselves) Tinder is strictly photo-based. There is no list of the person's favorite movies, no default menu of hobbies to select from, no "looking for" filters beyond gender and age range. Users see only the person's first name, age, distance from their location, photos, and mutual Facebook friends or interests.

Tinder came out of IAC's research and development arm. "We keep it sort of on the DL because it's much sexier for it to be a totally fresh startup that has nothing to do with the market leader," says Sam Yagan, CEO of IAC's Match.com and of OkCupid. "But we're constantly trying to build new startup-y stuff at Match, and this is a product that we started working on late last year with the team in L.A., and it popped." In Yagan's view, it's the user experience that has hooked people. "News Feed is one of those things that comes to mind, that has now become ubiquitous. Instagram had some UX attributes that made it addictive. Tinder has that," he says. Tinder declined to release download figures but claims 58 million matches have been made, out of 5.8 billion ratings. Co-founder and CEO Sean Rad claims he's heard of 20 engagements resulting from using the service.

MORE: Big in China: Jumbo shrimp pizza and green tea Oreos

There have been a number of similar apps and web sites. Bang with Friends is aimed at those interested in having sex; Coffee Meets Bagel books a lunchtime date; Kisstagram is a contemporary "Hot or Not" based on Instagram. Some have created controversy, and Tinder itself has achieved its success as what could be called a "hookup" app. (Rad rejects that term.) "My experience has been that when I'm chatting with a girl on Tinder, we both really know what we're there for," says Matthew E., a 25-year-old student in New York. He estimates he's gone home with 70% of women he's met up with from the app. "Nobody takes it very seriously, and that's what makes it great."

Now Tinder is trying to change that image by adding new features. First, its latest update includes something called Matchmaker, which allows you to connect two friends with an introductory note; they can then chat within the app. While it can be used to set people up romantically, Tinder hopes it also will be used for non-romantic purposes. Another update in the near future will offer up a sort of duplicate version of the dating section, but under a business heading; users will continue to see photos, but they'd be judging people on whether they'd make an appealing business connection. So, you'd see a photo of a man as well as a brief synopsis of his work background; he might be a consultant with McKinsey. Click him, and here you'd see a bit more of his work experience.

Rad insists he doesn't see Tinder as a dating app—and never did. "The long-term vision," he says, was always "for you to use Tinder to find new people for any purpose." He's aware of the light in which some see Tinder, but argues that the app is whatever you make of it: "There are people who just want to hook up and then there are guys who either knowingly or unknowingly are finding a wife. All we do is open up a chat box."

One obstacle to this shift appears to be age; the average Tinder use is 27, many of them in college or just out and uninterested, for now, in making business connections. But users will be able to opt out of the dating part—the app will be like a two-section bar where you can enter the fray of the singles lounge or stay in the quieter front area with the adults. Rad suggests that people will use Tinder not just for dating or for business, but for anything convenient, like when you're looking for a tennis partner: "Is the 60-year-old grandpa going to use Tinder? Well, I think it just comes down to, did his friend find a tennis partner on there."

MORE: Apple trial: Enter Amazon

Even Yagan sees Tinder as a dating app, for the moment. "Right now what we know is that Tinder is great for dating," he says. "Can it grow into something much bigger than that? Sure, it's possible. But my recommendation to Sean has been, 'Stay focused on the gold that you struck. If you can go to something bigger and better, hallelujah, but that's much more long-term." Tinder doesn't make any money yet, but could, Rad believes, by layering on "premium content" available at a cost. (He says there will never be ads.)

What's next? One imagines Tinder could eventually add buttons that make users' responses even more direct: I Am Not Single But I Get a Thrill From Using This; I Am Single And Looking for a Relationship; I Purely Want to Have Sex, etc. As for whether the app's name could take on a more serious association, it's possible, but will be tough. "My friends and I see it as a game," says Julianne Adams, a 21-year-old college student in New York. "Considering its superficial foundation, I hope Tinder never becomes a hiring tool."

Verizon extended its exclusive deal with the NFL to stream live games

Verizon extended its exclusive deal with the NFL to stream live gamesVerizon extended its exclusive deal with the National Football League yesterday, which for the first time will include the ability for subscribers to stream Sunday afternoon games and playoffs on their phones.

Beginning in the 2014 season, football fans with Verizon (VZ, Fortune 500) phones will be able to watch the home-market feeds of CBS (CBS, Fortune 500) and News Corp.'s (NWS) Fox Sunday afternoon NFL games via Verizon's NFL Mobile app. The new deal also will allow Verizon customers to stream all playoff games, including the Super Bowl.Verizon customers will continue to be able to watch nationally televised games on Thursday night,

Sunday night, and Monday night, which was part of the previous streaming deal inked between Verizon and the NFL.

The media-streaming deal will cost Verizon $1 billion over the next four years, according to Sports Business Daily. It was previously paying about half that amount annually.

That would make the new media-streaming deal one of the world's largest.

The field of broadcast shows signing deals with online partners has been steadily growing. In April, Yahoo (YHOO, Fortune 500) inked a deal with Comcast's (CMCSA) NBC to exclusively stream "Saturday Night Live" skits for one year.

Related Story: Will broadcasters beat Aereo at its own game?

For the 2013 season, Verizon will launch an updated version of its NFL mobile app which provides access to news, stats, game highlights, and on-demand videos in addition to live-streamed games. The basic, free app is available on phones and select tablets but does not provide access to live-streamed games.

Currently, Verizon customers must pay $5 monthly for the premium app allowing them to watch the games live -- a feature only available on phones

The unique facts of Apple's case will make it a singularly sympathetic one to today's markedly pro-business Supreme Court -- if the case reaches it.

FORTUNE -- After Monday's opening statements in the government's federal antitrust case against Apple -- stemming from Apple's game-changing foray into the then nascent ebooks market in 2010 -- it's apparent that the case raises novel legal questions that could well end up commanding the attention of the U.S. Supreme Court.

For casual observers of the case, this had not been so obvious before. That's because the legal questions raised by the conduct of the five publishing companies who were also originally named as Apple's

(AAPL) co-conspirators and co-defendants in the case -- Hachette, HarperCollins, MacMillan, Penguin, and Simon & Schuster -- did not pose comparably challenging questions. (Each publisher settled before trial admitting no wrongdoing.)

Unlike Apple, the publisher defendants were charged with engaging in a horizontal price-fixing conspiracy -- a well-recognized, frequently encountered, and widely condemned variety of collusive behavior. While the publishers' motivations may have been unusual -- some would argue laudable -- there is much evidence that they did, in fact, collude to hike up the price of ebooks. Under Section 1 of the Sherman Act, which forbids conspiracies "in restraint of trade," that's hard to justify.

In contrast, though, Apple had a vertical relationship to all the other players in the alleged plot. As a result, its conduct poses far less familiar factual and legal questions. While there have been prior cases in which vertical players have participated in horizontal antitrust conspiracies, these have usually involved situations where a behemoth vertical player was the instigator and chief beneficiary of the whole scheme -- the "ringmaster," as courts have put it.

Apple doesn't fit that template, though. Far from being a dominant player in the book industry, Apple was a new entrant. Far from instigating the scheme, it was -- even on the government's view of the evidence -- an opportunistic late-comer who exploited a preexisting situation. Moreover, it's not at all far-fetched to believe that Apple behaved at all times in a manner that furthered its own independent, seemingly lawful business objectives: opening a digital bookstore. In the process, Apple brought competition to a market that was, prior to its arrival, dominated by an 80% to 90% near-monopolist, Amazon (AMZN).

The Supreme Court has expressed far more reluctance to intervene in alleged vertical price-fixing conspiracies than in horizontal price-fixing conspiracies, due to having much less confidence in the former context about what constitutes reasonable commercial behavior and wherein lies the public interest. (As recently as 2007, for instance, the Court overturned 96 years of precedent to declare that there was nothing illegal "per se" about vertical price restraints.) The unique facts of Apple's case will make it a singularly sympathetic one to today's markedly pro-business Supreme Court if the case eventually reaches them.

MORE: Meet the man who created the 'linchpin' of Apple's e-book strategy

The following basic facts appear to be fairly undisputed. In November 2009, just two months before Steve Jobs made his historic unveiling of the first iPad tablet on January 27, 2010, Apple's head of content, Eddy Cue, convinced Jobs to give the iPad e-reader functionality and use the opportunity to launch a digital bookstore, comparable to Apple's already successful iTunes and Apps Store. Jobs greenlighted the project. But while the new iBookstore would launch on April 3, 2010, Jobs wanted the key contracts with publishers signed by the time of his January iPad unveiling, so he could include it in his presentation. (In his opening, Apple lead lawyer Orin Snyder, of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, included a video excerpt from Jobs's masterful iPad launch. While it was a moving and bitter-sweet moment for many of the journalists and business people present, U.S. District Judge Denise Cote, who is hearing the case without a jury, seemed ominously cold during the clip.)

Cue began meeting the CEOs of the six major publishers in mid-December 2009, sent out proposed term sheets in early January, and finally reached signed contracts with five of the publishers over the final three days preceding his January 27 presentation.

Cue knew next to nothing about the book industry when he undertook his task in December, according to Snyder, the attorney for Apple. But one thing everyone knew by then -- because it had been the subject of major articles in the Wall Street Journal and New York Times during the summer of 2009 -- was that the publishing companies were, by this time, furious with Amazon about the rock-bottom $9.99 price at which it was selling the ebook versions of most of their new-releases and New York Times bestsellers.

Amazon then controlled about an 80% to 90% share of the ebook market, having helped pioneer that market with its November 2007 launch of the Kindle e-reader. Publishers sold Amazon the digital versions of their books using the same so-called "wholesale model" that they used for selling hardcover and paperback books to brick-and-mortar bookstores. Under that model, they'd sell the book to a retailer at about half the contemplated list price -- say $12.50 for a hardback with a $25 price printed on the jacket --affording the retailer the discretion to determine how much of a discount they'd offer off the list price, if any.

Contemplating a retail price of about $20 for a digital book -- about 20% off the standard $25 price for a new-release hardback -- publishers sold ebooks to Amazon under this wholesale model for about $10. To their horror, however, Amazon resold the ebooks to the public for $9.99 -- a slight actual loss or, as U.S. Department of Justice lawyer Lawrence E. Buterman put it in his opening, a "break-even" price. Buterman didn't explain why Amazon did this in his opening, but Amazon evidently viewed the low-priced books as a way to kickstart a new market and stimulate sales of its new Kindle devices. Publishers feared, however, that such a low price would pull down the price of hardbacks and paperbacks, diminish authors' royalties, torpedo the viability of brick-and-mortar bookstores, and possibly lead to the elimination of publishers altogether (disintermediation) as ebook distributors like Amazon would begin contracting directly with authors.

In response, some publishers chose to raise their wholesale ebook prices to $12 or even $15, but Amazon continued to sell even those ebooks for $9.99 -- now absorbing a $2 to $5 loss on every single book sold. Government attorney Buterman glossed over Amazon's below-cost pricing without comment, though such pricing in other contexts, at least in the past, has been itself branded an antitrust violation ("predatory pricing").

MORE: The DOJ is arguing the facts. Apple is arguing the law.

Cue and Jobs.

Some publishers began withholding ebooks from Amazon altogether, or adopting "windowing" policies, where they would delay releasing an ebook until a certain number of months after the hardcover release. Some of Amazon's ebook competitors, like Barnes & Noble (BKS), also complained that Amazon's below-cost pricing was enabling it to monopolize the market and exclude would-be market entrants.

This brouhaha was widely known and reported as it was happening. What was less known at the time was that by the summer of 2009 the CEOs of the six major publishing companies had also begun meeting in private to discuss the future of their "industry" and what could be done about Amazon's $9.99 pricepoint. There is evidence that they tried to keep these meetings secret, presumably out of concern that the discussions might be thought to violate the antitrust laws.

"I think it would be prudent for you to double delete this from your mail files when you return to your office," one high-level Hachette executive told another at the close of an August 2009 email discussing conversations with other publishing houses, for instance.

If the publishers' meetings during the summer of 2009 did, in fact, constitute an antitrust conspiracy, however, there is no question that Apple was not part of it -- at least not yet. Eddy Cue, Apple's head of content, had not even conceived the notion of going into the ebook industry until November 2009, Snyder contends.

Apple also contends that it never knew about the extent of the publishers' horizontal collusion with one another, which seems both plausible to an extent, and implausible to an extent. Part of the problem here is that the concept of "collusion" is a funny one in the antitrust context. Whenever a traveler compares airline fares between two cities at a desired departure time, for example, he usually finds that all the key competitors charge exactly the same price -- down to the penny. That's not illegal price-fixing, so long as one Airline A set its price first, and Airlines B and C simply chose to match that fare later. If, on the other hand, all the competitors agreed beforehand that Airline A would announce its price first and that the others would then purport to "match" it after the fact, that's illegal price-fixing. It's a fine line for pragmatical, aggressive, business people to observe.

The government's theory, in any case, is that once Apple did decide to get into the ebook business, it learned of the conspiracy and then exploited it. Apple gave the publishers a way to force Amazon to abandon the wholesale model, and to impose a new "agency" model on the entire ebook industry. This was "a deliberate scheme orchestrated by Apple to fix prices," Buterman said on Monday.

MORE: The DOJ's antitrust case against Apple Inc. in 81 slides

Under the agency model, book publishers would set the retail price of the book themselves, and Apple would take 30% of the revenue as its commission (as it already was doing with its iTunes and App stores). Thus Apple joined the publishers' scheme, Buterman said, "as a quid pro quo to ensure they'd enter the market with guaranteed 30% margins and without price competition."

The government theorizes that no publisher acting alone had the leverage to force Amazon to abandon the wholesale model, but that five major publishers acting in concert did have that leverage, and that Apple was the crucial "go-between," "facilitator," or "ringmaster" that could orchestrate this united effort. The government will point to some emails between Apple's Cue and individual publisher CEOs in which Cue appears to reveal, when prodded, how many other publishers have committed to sign, or are likely to.

When Cue circulated the original proposed "agency model" term sheets to publishers in early January, each included a bullet-point stating that "all resellers of new titles must be in agency model." Thus, the government argues, Apple was requiring each publisher to insist that it alter its relationship with

Amazon -- abandoning the wholesale model.

Negotiations continued, however, and by the time contracts were signed in late January, there was no provision in any of the publisher's contracts with Apple explicitly prohibiting anyone from using the wholesale model with other retailers if they wished. Instead, there was a so-called "most-favored nation" clause (MFN), which is a fairly common feature in distributors' contracts. This clause provided that if some other retailer was selling an ebook for less than a publisher wanted to sell it at Apple's iBookstore, Apple was free to match that lower price.

So the MFN did not literally require publishers to abandon the wholesale model, though it certainly incentivized them to do so. (Here's why: If a publisher allowed Amazon, under the wholesale model, to continue to sell one of its books at $9.99, Apple could do so, too, under the MFN. But now the publisher would be receiving in return from Apple only $6.99 [70 per cent of $9.99] rather than the $10 wholesale price it was used to getting from Amazon.)

In late January 2010, after signing its agency contract with Apple, Macmillan CEO John Sargent met with Amazon and demanded that it switch to the agency model of pricing (at least once the iBookstore got up and running in April). After a brief tantrum -- Amazon initially deleted the buy buttons from all of Macmillan's books on Amazon.com -- Amazon capitulated.

In April 2010, when the iBookstore opened, most new-release ebook prices for the five major publishers jumped from $9.99 to either $12.99 or $14.99. (Apple's agency contracts had included the $12.99 and $14.99 price caps on different tiers of books because Apple feared the publishers would otherwise charge more than the digital market would bear.)

MORE: U.S.A. v. Apple Day 1: Calling Eddy Cue

The final impact of the adoption of the agency model on prices is, nevertheless, sharply disputed. Apple's Snyder claims the evidence will show that the average prices for the categories of ebooks in dispute actually declined over the course of the alleged conspiracy. The government's Buterman said that these declines in average prices over time merely reflected "trends" that were already "under way before Apple entered the market."

In context, then, was Apple's inclusion of an MFN clause into its contracts with publishers illegal? That, after all, is the mechanism that eventually, if indirectly, led to the demise of the wholesale pricing model.

The government claims that it is. In its antitrust complaint it characterized Apple's MFN clause as "the key commitment mechanism to keep the Publisher Defendants advancing their conspiracy in lockstep." And in its pretrial memorandum of law the government argued: "Apple knew that . . . the retail price MFN would sharpen [publishers'] incentives to follow through on raising prices across all retailers."

Apple's Snyder, on the other hand, argued that "no court has ever held an MFN to be illegal." On its face, certainly, an MFN simply gives a retailer the right to offer consumers the lowest available price. How could that be illegal, then, Snyder asked rhetorically. The MFN, indeed, made Apple agnostic to whether the publishers continue to use the wholesale model with Amazon or any other retailer, he said, since Apple (and its consumers) would be guaranteed the lowest available price no matter what.

And while the MFN does, indeed, give each publisher who signs with Apple an incentive to stop using the wholesale model with Amazon or anyone else -- so what? The entry of a new competitor into a market always changes every market participants' incentives.

"I'm aware of no antitrust case that's been based on 'sharpening another company's incentives,' " he said in his opening. "What does it even mean 'to sharpen incentives'? . . . That's no standard at all?"

MORE: Apple's day in court

In apparently having made an MFN clause the lynchpin of its conspiracy theory, the government may face another hurdle as well. At least according to Snyder, the evidence will show that each of the publishers during the negotiation process resisted the inclusion of that clause in their contracts with Apple. Snyder claims, for instance, that Hachette initially deleted it from the contract, calling it a "deal-breaker." HarperCollins CEO Brian Murray refused to sign until Steve Jobs went over his head, to News Corp. executive James Murdoch, and persuaded Murdoch of the wisdom of the deal. Random House, the largest publisher in the world, refused to ever sign Apple's agency contract, at least in part due to the presence of that clause, Snyder claims. (Random House was never named as a defendant in the government's case.)

"Each [publisher] was negotiating against the provision that supposedly held this conspiracy together," Snyder contended in his opening. "The publishers opposed the very contract term that the United States says was the secret sauce, the magic bullet … that enabled the conspirators to kill the $9.99 price point."

Of course, it remains to be seen whether, over the next three weeks of trial, the evidence will in fact come in the way Snyder has promised that it will, or whether it will, in the end, conform more closely to the more damning narrative predicted by Justice Department attorney Buterman.

Yet even though it's still hypothetical, highly contingent, and years down the road at best, it's hard not to already hear Justice Antonin Scalia's taunting voice at an oral argument, caustically demanding: "Mr. Buterman, can you name another case in which we have held that a company violates the antitrust laws by 'sharpening the incentives' of a contractual partner to act in certain ways?"

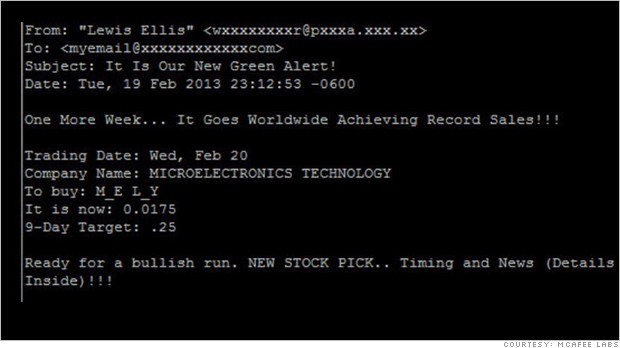

After years of declines, spam email is roaring back, and the culprit appears to be the booming stock market.

McAfee, Intel's (INTC, Fortune 500) security unit, reported this week that it counted 1.9 trillion global spam messages in March. While the number is not record-breaking, it is twice the volume counted in December.That's a stunning turnaround for spam, which has remained stagnant or on the decline for the past three years.

A major factor in spam's giant comeback is a significant increase in so-called "pump-and-dump" scams. In those fraudulent campaigns, scam artists tout a company as a hot stock to drive up the price. Investors lose money when the crooks cash out, sending share prices plummeting.

McAfee could not calculate the percentage of pump-and-dump type emails, but Worldwide Chief Technology Officer Mike Fey said it is "significant."

Related story: Gmail's new killer feature is spam blocking

The increase in investment-related spam comes at a time when the stock market has reached an all-time high. The bull market could add the appearance of legitimacy to the schemes, according to Heath Abshure, board president of the North American Securities Administrators Association.

McAfee analyzes abnormal bursts in traffic, determining what they are, where they are being sent, and

where the links could take the user.

In the recent spam spike, naïve investors have frequently been the target. One telling factor: Pump-and-dump schemes typically involve little-known stocks that are not listed on mainstream stock exchanges.

Abshure says he worries that once the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act gets a final stamp of approval from the Securities and Exchange Commission, it is expected to allow companies to advertise unregistered securities, worsening the spam problem.

The social-media-like products being planned by Dow Jones and Bloomberg are not attempts to take on the social media giants.

Lex Fenwick, the Wall Street Journal's publisher and the CEO of Dow Jones (NWSA), didn't even mention LinkedIn during the recent News Corp. investor presentation where he unveiled the social-media product, WSJ Profile (as first reported by the Times of London). That could be because he doesn't see LinkedIn as a competing product -- and it isn't, really. WSJ Profile seems to be merely a way for readers to set up personal pages on the Journal's website, access Dow Jones's various web offerings (such as Barron's, Dow Jones Newswires, All Things D's tech coverage, and Factiva), their own stock portfolios, and to interact with each other. Seemingly part of a larger strategy to unify Dow Jones's many platforms, it might be a good or a bad idea, but the presence of LinkedIn (or Twitter or Facebook or any other social media product) will have little bearing on whether it succeeds or fails. LinkedIn (LNKD) is mainly a career-focused site aimed at the general public. WSJ Profile seems to be more of a way for Dow Jones to extract more value from its own products.

MORE: Meet the OS Google and Apple should worry about

It's not surprising that the people who are always quick to champion "openness" and to favor social media over professionally produced media (even though the former relies so heavily on the latter) would see this as "the Journal vs. LinkedIn." But by all accounts, Fenwick was fairly clear about the company's intentions: WSJ Profile consolidates all of Dow Jones's services together and syncs brokerage accounts. It's designed to increase subscriber "stickiness" (a term left over from the dot-com boom that simply means keeping people on the site longer) and to better target ads based on readers' interests and behaviors.

Fenwick also mentioned how it helps Journal readers participate in the "sharing economy" (another rather hoary sounding term). That seems like a tertiary consideration, but people who value the Internet's ability to facilitate online yammering over its ability to disseminate valuable information are, unsurprisingly, more focused on the yammering part.

It's a little harder to tell what Bloomberg has in mind for Bloomberg Current, now in beta and with only a bare-bones sign-up page, but judging by this page created by its designers, it seems to be something similar: People set up pages for themselves with custom-designed news feeds and the ability to communicate with other users.

Again, this is being described as an also-ran competitor to LinkedIn and Twitter. Mathew Ingram of paidContent went so far as to say that "Bloomberg's core business is clearly threatened" by those two social networks, and he described Bloomberg Current as a desperate response to that threat. "Although the wire service has made the bulk of its multibillion-dollar revenues from selling its proprietary terminals," he wrote, "one crucial factor in the value of those terminals is the way they allow traders, brokers, and other financial professionals to connect with each other, send instant messages and so on. Real-time market data is also important, obviously, but those connections are gold."

MORE: This man wants to sell you a male wet nap

Well, no, the gold is in the data, and in the ability to manipulate and analyze it, as well as to execute trades (also, the wire service is really just an adjunct to Bloomberg's main business: its proprietary data service). For Bloomberg customers, data is much more than "also important" -- it's basically the whole thing. Few companies are going to shell out $1,500 a month per user just so employees have the ability to "connect" with people. Email, instant messaging, and message boards have been ubiquitous for nearly two decades, and they're all free. The Bloomberg terminal's facilitation of "connectedness" is just one, relatively minor feature of the product. Bloomberg Current, like WSJ Profile, seems like a way to appeal to everyday consumers of business news, whether they have a Bloomberg box or not. This shares some, but not all, of LinkedIn's features, and even fewer of Twitter's. It could turn out that the "closedness" of the service will appeal to people who might want to engage with others about business news but are turned off by the awful and annoying behavior that often comes with more "open" social networks like Twitter.

One aim of both of these products might be simply to enable salespeople to use the phrase "social media" when they're meeting with clients and potential clients. Whether the products will do much for either the Journal or Bloomberg is highly uncertain. Previous attempts by media companies to create

their own, social-media-like services haven't done so well. The best-known of them, the New York Times'

TimesPeople, was launched in 2008 and was killed three years later. But that was a very different endeavor from what the Journal and Bloomberg seem to have in mind. TimesPeople was more akin to social media networks as we know them, with an emphasis on general news. It enabled people to follow each other, comment on stories, and share their favorite items from across all of the Times' sections, from sports to international news to reviews of Broadway shows. Bloomberg and the Journal are much more tightly focused on actionable business news.

One other thing the Journal's effort should not be compared to: MySpace. News Corp. which owns Dow Jones and the Journal, purchased MySpace and mismanaged nearly all the value out of it before selling it off. But MySpace was a separate entity from all the rest of News Corp.'s products, and it was largely aimed at kids and young adults. It makes no sees to compare MySpace to WSJ Profile just because they're both vaguely involved with "social media" in some way. But that hasn't stopped people from making the connection anyway.

From trash pickup to ... zombie emergency preparedness.

FORTUNE -- On April 20, 2007, a young U.S. senator named Barack Obama sent his first tweet.

"Thinking we're only one signature away from ending the war in Iraq,"

the future president tweeted, a bit optimistically. Since then,

governments across the world have jumped onto social media. These days,

voters are as likely to see political ads in their Facebook feeds as on

TV, and Twitter Q&As with elected officials have become as common as

fireside chats.

But beyond the usual applications, governments are also experimenting with using social media in surprising, progressive, and sometimes just plain weird ways. I've seen it from the front lines working at a social media company that makes tools to connect governments and other organizations with millions of users. Specialized command centers can now monitor trends on Twitter and Facebook (FB) in minute detail, enabling officials to do everything from forecast voting patterns to anticipate disasters before they happen.

Here are 5 unusual and powerful ways governments are harnessing social media:

Picking up the trash: Anyone who's waited all day in line at the DMV knows that government agencies aren't always keen on customer service. But does it have to be that way? Take something as simple as weekly garbage collection. In the city of Vancouver, confusing schedules were leading to overflowing bins on streets and in homes. So the city turned to Twitter. It set up a website where residents could sign up to be tweeted the night before garbage and recycling collection. Specialized bulk tweeting and scheduling tools made it possible. Result: cleaner streets and sparkling customer service at a fraction of the cost of traditional phone centers or email.

Defusing riots: The 2012 London Olympic Games were largely free from disturbances and disorder. Could social media have played a part? Prior to the games, U.K. police set up a dedicated social media task force. Using social media management tools, they followed known rabble rousers on Twitter, setting up streams to monitor conversations about the games and planned protests. When push came to shove, authorities were able to dialogue with antagonists in real time and, in some cases, pinpoint the exact location of troublemakers using geolocation features. All of the information was open and publicly accessible: All it took was the right tools to tap into it.

Detecting earthquakes before they happen: When a 5.9-magnitude earthquake shook the Northeast in

2011, many New Yorkers learned about it on Twitter -- seconds before the shaking actually started. Tweets from people at the epicenter near Washington, D.C., outpaced the quake itself, providing a unique early warning system. (Conventional alerts, by contrast, can take two to 20 minutes to be issued.) Seeking to take advantage of these crowdsourced warnings, the U.S. Geological Survey is hard at work on TED, short for Twitter Earthquake Dispatch. It uses specialized software to gather real-time messages from Twitter, applying place, time, and keyword filters to create real-time accounts of shaking.

Preparing for the zombie apocalypse: Taking a page from Orson Welles, the Centers for Disease

Control recently terrified readers with a blog post titled Preparedness 101: Zombie Apocalypse. "[Where] do zombies come from, and why do they love eating brains so much?" the author asks, before listing ways to prepare for the inevitable. The post, which also explained how to get ready for real emergencies, attracted more than 1,200 comments, with a lively debate ensuing between readers on the finer points of zombie culture and emergency preparedness. While not a social network in the strict sense of the word, the CDC blog does illustrate how governments can use online channels to engage and educate. More recent posts have focused on what the popular board game Pandemic can teach us about how disease spreads.

Forecasting elections: During the 2012 U.S. presidential election, Twitter developed a brand new political analysis tool called the Twindex, which gauged online conversations and sentiment around Barack Obama and Mitt Romney. As election day approached -- and most traditional polls had Romney pulling ahead -- the Twindex showed Obama trending sharply upward in all 12 swing states. Now, it may have been pure coincidence that Obama went on to win. Or maybe not. It's hard to dispute that buzz in the Twittersphere is tied to real-world sentiment. As analysts get better at quantifying that buzz, social media may become a crystal ball of sorts for peering into election results. Many campaigns are already investing in social media command centers, specialized software and screens for tracking social mentions, and trends in detail.

With the right social media management tools, agencies and officials are turning the torrent of social posts into a catalyst for better government (or, at least, some pretty cool apps). Keep an eye on your newsfeeds: Big data plus better software means these initiatives could be coming soon to a social network near you.

Ryan Holmes is the CEO of HootSuite, a social media management system with 7 million users, including 79 of the Fortune 100 companies. In the trenches every day with Facebook, Twitter, and the world's largest social networks, Holmes has a unique view on the intersection of social media, government and big business.